Background Note

COVID-19 and the socioeconomic impact in Africa

The case of Ghana

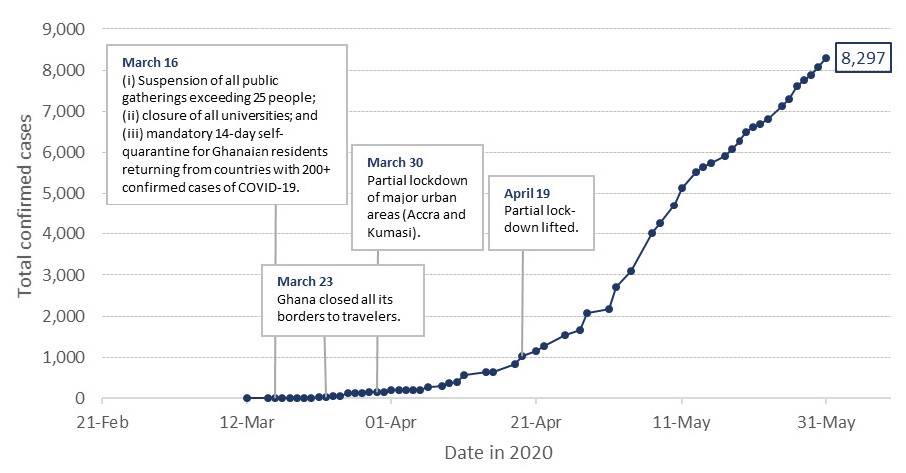

The first two cases of COVID-19 were reported in Ghana on 12 March 2020 by the health ministry. As a first response, on 15 March all public gatherings were banned, all schools and universities were closed, and on 23 March all of the county's borders were closed. In the interest of public safety, a partial lockdown was introduced on 30 March in areas identified as ‘hotspots’. This was lifted on 19 April, but as of this writing the other measures remain in force.

When lifting the partial lockdown, the president cited the country’s current capacity to trace, test, isolate and quarantine, and treat victims of the disease as one of the reasons for the decision. Nonetheless, the number of confirmed COVID-19 infections has been escalating. According to the Ghana Health Service, as of 31 May 2020, a total of 219,825 samples have been tested, 8,297 were positive (of which 5,798 are located in the Greater Accra region), representing 3.77 per cent of the sample, of which 2,986 have recovered, and 39 have died.

Figure 1: Total confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Ghana as of 31 May 2020

What has the government done with respect to COVID-19 measures of mitigation and suppression?

In response to the pandemic, the government set up an Inter-Ministerial Committee on Coronavirus Response chaired by President Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo. The key objectives of the committee were: limit and stop the importation of the virus; contain its spread; provide adequate care for the sick; limit the impact of the virus on social and economic life; and inspire the expansion of domestic capability and deepen self-reliance.

The chairperson of the committee swiftly announced some measures to contain the spread of COVID-19. Some of these measures include a travel advisory, which strongly discourages all travel to Ghana except for citizens and persons with residence permits. A mandatory 14-day self-quarantine and testing period for travellers entering Ghana was imposed. This measure proved to be very effective, identifying 105 of the 1,030 persons entering the country as carriers of coronavirus. In addition to suspension of all public gatherings and closure of all schools and universities, businesses and establishments—such as supermarkets or shopping malls that were allowed to operate—were advised to strictly observe enhanced hygiene procedures and social distancing.

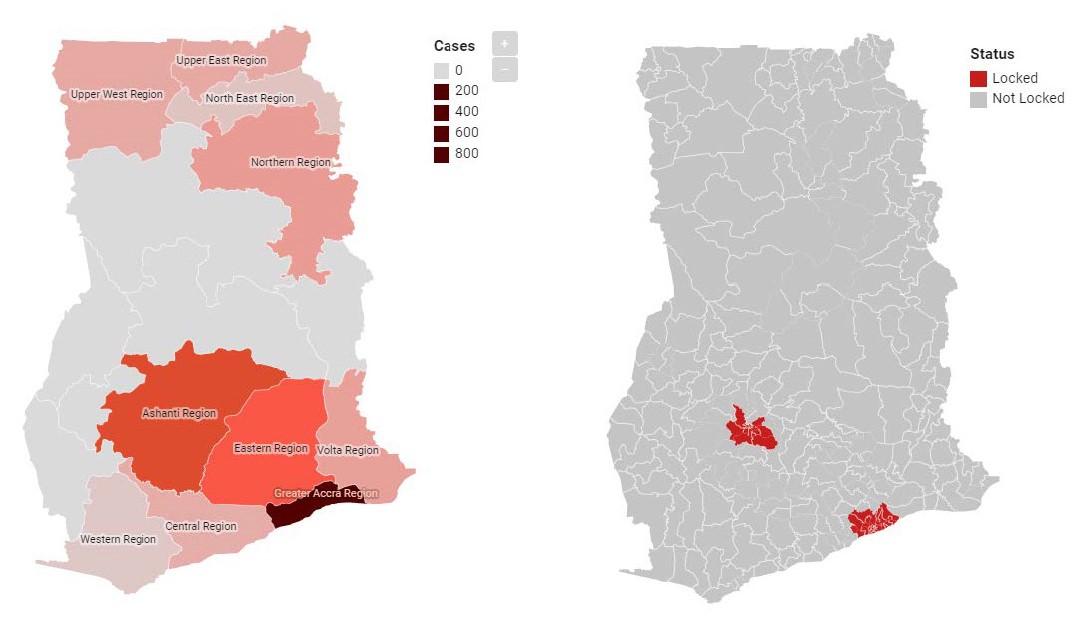

Figure 2: The COVID-19 situation in Ghana

Source: CitiNewsroom.com, coronavirus webpage.

The president announced, following an ongoing increase in the total number of cases, that there was the need to impose stricter measures, especially in Accra, Tema, Kasoa, and Kumasi, which have been identified by the Ghana Health Service as ‘hotspots’. A partial lockdown was therefore imposed on 30 March 2020 that restricted movement of persons in the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area (GAMA) and the Greater Kumasi Metropolitan Area and contiguous districts, for a period initially of two weeks but ultimately lasting until 19 April; see trajectory of active cases and areas of lockdown in Figures 1 and 2.

The lockdown was largely meant to facilitate the scaling up of effective contact tracing of persons who had come into contact with infected persons, test them for the virus, and, if necessary, quarantine and isolate them for treatment. In order to accelerate the scaling up of contact tracing capacity, the military and police were drafted in to assist health authorities. The policy of tracing and testing all contacts of people tested positive was also introduced. One thousand community health workers and an additional thousand volunteers were recruited and adequately resourced to work effectively.

While the partial lockdown was lifted on 19 April, the suspension of all public and social gatherings was extended and remained in effect through May 2020. On 31 May, President Akufo-Addo outlined a phased easing on the restrictions to occur over the next month, including the permission of public gatherings with a maximum attendance of 100 persons with appropriate social distancing precautions beginning 5 June, and the re-opening of junior and senior high schools and universities starting 15 June. Large sporting events, political rallies, festivals, and religious events remain suspended until 31 July. Nightclubs, bars, beaches, and cinemas will also remain closed during that time. In addition, the general public is encouraged to wear face masks when going out, and the Regional Coordinating Councils mandates the use of face masks in public for the Greater Accra, Ashanti, and Central Regions. Ghana’s international land, air and sea borders will remain closed to human traffic until further notice.

What are the economic implications of the pandemic on the poor and most vulnerable?

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has posed a major disruption to economic activity across the world. According to recent World Bank estimates, ‘economic growth in sub-Saharan Africa will decline from 2.4 per cent in 2019 to -2.1 to -5.1 percent in 2020, the first recession in the region in 25 years’. Given that crude oil exports have contributed greatly to Ghana’s economic growth over the past decade, accounting for about 20 per cent of total export revenues in 2018, the country’s economy may be particularly hit in a context of declining commodity prices. Cocoa, another important export product of Ghana, also saw its prices fall. On the other hand, as the top producer of gold in Africa, Ghana’s economy may benefit from the rise in gold prices that, over the past months, have surged to their highest levels since 2013. Ultimately, the effect will also depend on how the country’s top trading partners and providers of foreign direct investment—India, China, the USA—weather the crisis.

Beyond the drop in commodity prices and external demand, workplace closures and travel bans will impact the national economy. In this light, Ghana’s finance minister adjusted the country’s economic growth forecast for 2020 downward, from an initial projection of 6.8 to 1.5 per cent—which would be the country’s lowest growth rate in 37 years—under the scenario of a partial lockdown of the economy. Generally, government restrictions on mobility and the adopted social distancing measures imply a slowdown in production alongside the total suspension of some activities. This reduces working hours and labour earnings, and results in a reduction in aggregate demand for goods and services.

The COVID-19 pandemic thus poses important risks, not only for people’s health but also for their economic wellbeing. Already disadvantaged groups will suffer disproportionately from the adverse effects. Low-income earners, especially informal workers, who earn a living on a day-to-day basis and have limited or no access to healthcare or social safety nets, are severely hit.

Informal sector businesses are like any other businesses. With COVID-19 bringing transportation and market demand to a halt informal sector businesses, such as drinking and chop bars, small retail shops, hairdressers, and taxi drivers will see a reduction in customers because of the pandemic. This may extend beyond the lockdown, for example if customers continue to avoid crowded markets and if the economic downturn has lasting consequences for household spending. Moreover, cross-border traders still cannot operate and street vendors and market traders who sell products other than food remain restricted in their activities. Similarly, as care workers in households, many informal employees are particularly vulnerable to contracting the virus. Many of the most vulnerable are facing an explicit tradeoff between their health and their financial survival.

The pandemic response measures may also aggravate gender inequalities in employment. Not only are the smallest and most vulnerable businesses often run by women, but women will also be disproportionally affected by school and daycare closures and often exit the labour market to care for children or sick relatives.

What supporting measures did the Ghanaian government take to protect the poor and the vulnerable?

The finance minister was tasked by the president to prepare and present to parliament a Coronavirus Alleviation Programme (CAP) to address the disruption in economic activities, the hardship of the people, and to rescue and revitalize industries. The CAP included the following measures:

- A minimum of GH¢1 billion was to be made available to households and businesses, particularly small and medium-scale enterprises (SMEs).

- In responding to the Bank of Ghana’s 1.5 per cent decrease in the policy rate and 2 per cent in reserve requirement respectively, commercial banks will provide a GH¢3 billion to support industry—particularly in the following sectors: pharmaceutical, hospitality, service, and manufacturing.

-

Additional relief to be provided by government:

- extension of the tax filing date from April to June

- a 2 per cent reduction of interest rates by banks, effective 1 April 2020

- the granting by the banks of a six-month moratorium of principal repayments to entities in the airline and hospitality industries, i.e. hotels, restaurants, car rentals, food vendors, taxis, and uber operators;

- mobile money users can send up to GH¢100 for free; and

- a 100–300 per cent increase in daily transaction limits for mobile money transactions.

- The establishment of a COVID-19 fund, to be managed by an independent board of trustees and to receive contributions and donations from the public, to assist in the welfare of the needy and the vulnerable.

- The ministries of gender, children and social protection, and local government and rural development, and the National Disaster Management Organization (NADMO), working with Metropolitan, Municipal and District Chief Executives (MMDCEs) and faith-based organizations at the district and local level, will provide food (dry food packages and hot meals) for up to 400,000 individuals and homes in the affected areas of the restrictions.

The Ghana Water Company Ltd and the Electricity Company of Ghana were directed to ensure a stable supply of water and electricity during the lockdown period. In addition, there was no disconnection of supply. Government will absorb the water bills for all Ghanaians for the three months of April, May, and June. All water tankers, publicly and privately owned, will be mobilised to ensure the supply of water to all vulnerable communities. Government will also fully absorb electricity bills for the poorest of the poor, defined as lifeline consumers who consume zero to 50 kilowatt hours a month for this period. For all other consumers, residential and commercial, government will also absorb 50 per cent of electricity bill for this period. This is being done to support industry, enterprises, and the service sector in these difficult times, and to provide some relief to households for lost income.

Government, in collaboration with the National Board for Small Scale Industries (NBSSI), Business & Trade Associations and selected Commercial and Rural Banks, will roll out a soft loan scheme up to a total of GH¢600 million, which will have a one-year moratorium and two-year repayment period for micro, small, and medium-scale businesses.

What needs to be done more to protect the poor and vulnerable?

There is a need to do more in order to provide adequate relief to the poor and vulnerable—quickly, safely, and effectively. To restore income, preserve livelihoods, and compensate for price hikes, direct cash payments to those in need are crucial. In countries with broad-based social protection systems, such as South Africa, a scaling up and re-purposing of existing grants as emergency relief can be effective. Yet, in Ghana, such systems remain limited in coverage and will need significant upgrading to respond to the pandemic. Specifically, the Livelihood Empowerment Against Poverty (LEAP) programme, which provides cash and health insurance to extremely poor households, has little presence in urban areas. It is now necessary to expand the LEAP programme to urban areas, especially in ‘hotspots’.

The current proxy means test for the LEAP programme, which is focused more on the rural poor, should be carefully adjusted so that it also targets poor households in urban areas—especially those with children and elderly members. The provision of transfers to cover basic needs would make it easier for risks groups to stay home and reduce activities that are likely to further spread the disease.

Certainly, from a public health perspective, the lifting of the partial lockdown must be considered premature. It has not lasted long enough to flatten the pandemic curve. Instead, the number of confirmed COVID-19 infections continued rising during the lockdown and has doubled since, which threatens to overwhelm the country’s poorly resourced medical infrastructure.

However, in Ghana, the lifting of the lockdown was not just a choice between lives and economy, but a choice between lives and lives. Distributed food supplies have not reached everyone, and people are getting desperate. In order to prevent an escalation of infections there is the need for the government to develop and deploy suitable and effective social influence strategies at this stage of the fight against the pandemic. The government should continue working with all relevant stakeholders, including leaders of faith-based organizations, the security forces, the Ghanaian media, and national institutions such as the National Commission for Civic Education and agencies under the Ministry of Information. Some of the strategies can focus on persuading the population to conform to wearing face masks, washing hands and using hand sanitizers, and practicing social distancing, among others.

The stimulus package announced by the government should target and support essential SMEs—SMEs that provide inputs and services to support other SMEs—and particularly the agricultural sector. SMEs that have immediate demand for their products and services and the potential to create jobs must also be supported. There is also the need to ensure that disruptions to farmers’ access to inputs, such as seeds, fertilizers and insecticides, are eliminated.

Join the network

Join the network