Research Brief

What is the Effect of Aid on Primary Enrolment and Quality of Education?

- An increase of education aid by one per cent increases the rate of primary education enrolment by 0.06 percentage points.

- The most robust effect on primary enrolment is obtained by aid to the category ‘education facilities and training’.

- High levels of education aid in the last decades concentrating on school enrolment has resulted in more children going to school. The challenge for the years to come is how to improve the quality of instruction.

- High aid disbursement with unequal shares going to different sectors of education has been found to lead to lower quality learning.

The achievement of universal primary education by the year 2015 by all countries was one of eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) set by the international community in 2000.

Since then international efforts have intensified and increased amounts of aid have been channelled to some of the world’s poorer countries in order to help them meet this target. Experience from the last decade indicates that this effort has been effective; a sizeable share of the progress towards universal primary education is due to a tremendous increase in education aid disbursements by donors.

The most recent evidence finds that increased aid disbursement for education lead to an increase in primary education enrolment, which is consistent with previous studies which have found a strong correlation between aid disbursement and increases in primary education enrolment. In general, doubling annual education aid per capita for a period of five consecutive years leads to a nearly six per cent rise in net enrolment rates. The impact is modest but by no means negligible.

In spite of the positive correlation between increased education funding and primary education enrolment evidence suggests that raising the enrolment figures does not always lead to an improvement in the quality of education.

Achieving high levels of primary enrolment

The impact of aid disbursements on primary education should be considered not in isolation but take into account the interaction between different sub-categories of the education system as a whole. Some sub-categories complement each other and funding in one subcategory may produce spillover effects elsewhere in the education sector.

For instance, a UNESCO report found a link between pre-primary education and the ability to cope well during later years in school leading to lower drop-out rates. There also appears to be a complementarity relationship between primary and secondary education whereby, if funding for primary education is increased while supporting secondary education, it further enhances primary education enrolment. A well-functioning secondary (or even tertiary) education system may enhance students’ incentives to complete primary school.

For instance, a UNESCO report found a link between pre-primary education and the ability to cope well during later years in school leading to lower drop-out rates. There also appears to be a complementarity relationship between primary and secondary education whereby, if funding for primary education is increased while supporting secondary education, it further enhances primary education enrolment. A well-functioning secondary (or even tertiary) education system may enhance students’ incentives to complete primary school.

Other subcategories in the education sector, in particular ‘education facilities and training’, ‘teacher training’, and ‘basic skills’ appear to have a direct influence on primary school enrolment, and so funding for these should be taken into account when increasing funding for primary education.

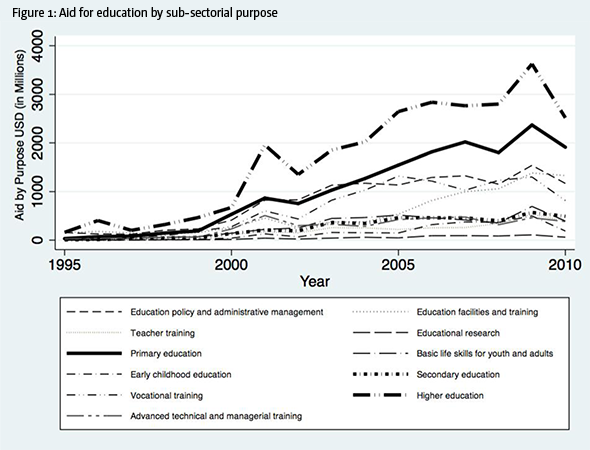

As the figure below shows tertiary education has received higher funding than all sub-categories since the mid-1990s, and even after the MDGs were agreed upon it has received more funding in general then primary education, which is rather surprising given that the current objectives place far more on the latter.

Secondary education has benefited much less from the general increase in funding, and this might constitute a bottleneck in the future for primary education enrolment since funding for secondary education appears to further enhance the incentives for completing primary education.

The challenge: raising quantity without sacrificing quality

The challenge: raising quantity without sacrificing quality

As policy makers continue to pursue the goal of increasing primary education enrolment, it is good to keep in mind that there is a complex relationship between education quantity and quality. Being able to learn, understand texts, and carry out essential arithmetical operations, is after all the ultimate goal of primary education. The fact that children are spending several years in school does not necessarily mean that they are able to perform these tasks.

In five out of eight sub- Saharan Africa countries where household surveys on literacy information were conducted, it was found that less than 50 per cent of children who have spent five years in school were able to read a few sentences. Similarly, evidence from Mozambique, Kenya, and Malawi suggests that significant improvement in school enrolment was not accompanied by corresponding increases in national reading scores, but rather decline or stagnation.

It is clear that a major challenge facing policy makers has been, and continues to be, how to find a balance between increasing enrolment while at the same time maintaining and raising the quality of education. International donors have often put pressure on recipient governments to simply increase school enrolment. That policy may have been counterproductive since it might end up emphasising quantity to the detriment of quality.

- Aid to secondary education could be increased to attain higher primary enrolment rates due to the significant complementarity between primary and secondary education.

- Priorities to increase primary school enrolments have undermined the quality of education.

- Quality of primary education is best supported through aid with balanced funding of the whole sector.

The total amount of aid disbursed does not have relevance for raising the quality of education, but how that aid is distributed within the sector is significant. Evidence suggests that in order to address the issue of quality with regard to aid disbursement, there should be a more equal spread of aid to education across the sector; i.e., between those directly related to primary education on the one hand, and those related to higher levels of education on the other. Nevertheless, the distribution of aid alone cannot guarantee the simultaneous increase in quality and quantity—it remains ultimately a challenge for national policy makers to overcome.

Join the network

Join the network