Blog

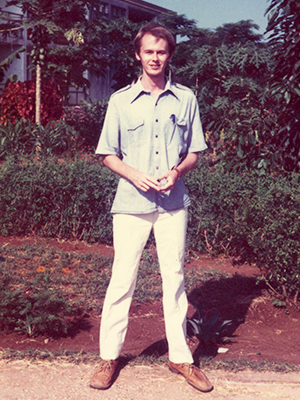

Miner’s son turned mining researcher

Tony Addison is the first in his family not to become a miner. He has decades of experience in development economics and economic reform in developing countries.

It was a rainy day in London at the turn of the 1980s. Twenty-year-old Tony Addison had been wandering around the streets when he found himself standing in front of a certain doorway and noticed an announcement, which was to determine his future career.

The announcement was a call for young economists to go and work in Africa.

’So I went to Tanzania to work at the Ministry of Industry and Trade for two years. At the time, Tanzania was experiencing a severe financial crisis. Through practice, I learnt the importance of economics to a developing country’, Addison recalls at his office in Katajanokka, Helsinki.

Addison works at the United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics (UNU-WIDER) as the Chief Economist and Deputy Director.

'The Tanzania years were fantastic. I remember vividly what it was like to travel through villages with loudspeakers blasting Bob Marley, music from the local bands or Abba.’

That period was heavily marked by the ideological struggle of the Cold War. In addition to the Western donors, many of the socialist states were also represented in Tanzania, from the Soviet Union to North Korea.

Addison is grateful for the British Overseas Development Institute’s (ODI) Fellowship Scheme, which enabled him to go abroad.

‘The programme has been around since the beginning of the 1960s. It has enabled posting young economists to work in the public sector in developing countries, in Africa for example. It has been running for so long that we now see the grandchildren of the first participants taking part in the programme.’

Learning from a crisis

After returning to the UK from Tanzania, Tony Addison graduated from university and took a job as a researcher at the ODI’s London office. Throughout the 1980s he continued to work mostly with issues to do with Africa.

'At that time, two big things happened in Africa. One was the macroeconomic crisis, which was very serious. I witnessed it closely in Tanzania. We, the economists of my generation, were trying desperately to learn from the situation and come up with solutions for bailing out the states’ economies.

There were many reasons for the economic difficulties, including heavy reliance on agriculture, rapid population growth as well as cuts in Western development aid and in the contributions given to the World Bank, especially in the early years of the 1980s. The economy was also affected by the unstable social and political development.

Another major phenomenon defining the era was the emerging globalization. Addison explains how the rise of the Asian economies gradually became evident, and the contrast with development in Africa was striking.

‘The population in Africa today is so young that they themselves do not remember the events of the 1980s. However, remembering would be important, because it is about avoiding the mistakes made at the time as well as avoiding a similar economic crisis.’

After leaving the ODI, Addison taught development economics as his main job at the Warwick University in the UK in the 1990s.

‘In my opinion we did a great job with the teaching. For example, two of our students are now in the World Bank leadership team. I just saw them at an international conference where they were seated in the front at the key seats and I was at the back amongst the audience. I am very proud of them.’

Fragile peace

In addition to his teaching work, Tony Addison held many expert positions including World Bank projects especially in southern Africa. During those years he was working in Mozambique, for example, where a peace treaty was signed in 1992, and the country was trying to get back on its feet after years of war.

’I was working on poverty-related issues at the Ministry of Finance. We were putting together the first poverty reduction strategy for the country and looked for funding for the reconstruction’”.

There was still a sense of fear in the air that the country would slip back into conflict in such a fragile situation.

’It was fascinating to ponder how to stabilize the country and sustain peace. How do we move from widespread internal displacement to resettling the population, and how do we make the society to function again? Of all the work I have done, I am perhaps the proudest of my time in Mozambique.’

Addison’s life was busy and he was not short of interesting assignments, but he could also not help but think about the next potential challenges. He had already got to know the Director of UNU-WIDER at the time, an Italian economist Giovanni Andrea Cornia, who eventually lured Addison to Helsinki.

‘I had never been to Finland before. As a boy I collected stamps and I had a few sheets of Finnish stamps. It was all that Finland meant to me.’

Addison came to visit Finland in January-February 1997. He was met by a very cold and snowy winter. He remembers walking down the empty streets of Helsinki and wondering how on earth anyone could live here.

’But I came back in the summer. I sat down with a beer in Suomenlinna and said that this wasn’t too bad, after all. So I moved here from Warwick with my wife Lynda.’

During his first term at UNU-WIDER Addison focused mostly on issues related to post-conflict reconstruction. The situation in West Africa in particular had not stabilized by the late 1990s, with conflicts tearing up Liberia and Sierra Leone, for example. It was looking like Mozambique was going to be a one-off success story.

’Today and all too often, we take peace for granted. Peace is truly fragile. I have seen and experienced it in Africa.’

International cooperation is definitely a key to peace and along with it for a positive societal development, Addison stresses.

’I am a great supporter of the UN system. Despite its problems it is the only system that brings together nations very different from each other. When someone criticizes the UN system to me – often for a good reason – I say “Look what we had before it”’.

Energy revolution

Tony Addison worked in Helsinki for eight and a half years and then returned to the UK to be a professor of development economics at Manchester University. In the following years, he was involved in founding the Brooks World Poverty institute, which specializes in poverty research.

However, in 2009 he permanently returned to UNU-WIDER, now as a Chief Economist and Deputy Director. In recent years his work has focused on issues such as foreign aid and its impact, as well as taxation issues.

Tony Addison has worked as an economist specializing in development issues for 39 years. ’However, my main work has dealt with the extractive industries, i.e., oil and gas production as well as the mining industry. The topic is very controversial, and the mining industry, in particular, does not have a good reputation because of its adverse effects on local communities and the environment.’

The extractive industry has many links to both development issues as well as climate change. For example, switching to wind and solar-powered energy sources as well as to electric cars will help combat climate change, but at the same time the problem is that storing renewable energy and using electric vehicles requires lithium-ion batteries.

The extraction and further processing of the raw materials needed for lithium-ion batteries causes CO2 emissions and environmental damage. Furthermore, recycling of metals is still non-existent.

‘The challenge is that we don’t have the technology required to respond to climate change as quickly as we should. Universities and businesses have a very important role to play here in finding new ways to store renewable energy, for example. We need young, smart people to solve these issues.’

Miner’s son

Talking about the extractive industry leads us back to London and the young Tony Addison, who was standing in front of a notice advertising job opportunities in Africa. A career as an economist was by no means an obvious choice for Addison, as he comes from a family with a strong working-class background.

’The Addisons, and also some of my relatives on my mother’s side, have been earning a living at the County Durham coal mines since the early 19th century. I am the first Addison who does not dig coal.’

Addison’s father started in the mines at the age of 14 in the 1930s. For a long time the coal mining industry was one of the largest employers in Britain. In the 1950s, for example, approximately one million Britons worked in mines. Today, coal mining has almost ceased.

‘The UK is very much a class society, but in my youth the idea of social mobility was thriving. If I recall correctly, my age group, those born in 1958, have been the most successful in climbing the social ladder.’

According to Addison, his generation benefitted particularly from free education and good-quality healthcare in the 1960s and 1970s Britain. He sought career counselling twice, and on both occasions it was suggested he become a policeman. The first time it happened he was at school.

‘The second time was at the university. I told the counsellor that I had been thinking about a career in the academia, but she responded that one does not always get what one wants in life. Then she asked if I had thought about joining the police force. I am sure that a career as a policeman is a fine one, but all I could think of were the policemen in the books who were a bit dumb, to whom Miss Marple or Hercule Poirot had to explain everything.’

What on earth shall I do with my life, Addison had been agonizing over until he came across the ODI fellowship notice.

‘I went to Tanzania in 1980, meaning I have been working as an economist specializing in development issues for 39 years now. My goodness, has it been so long already!’

Next year, Addison turns 62 and will retire from the UN. However, he does not intend to give up working with development issues but continues to work on his research on the extractive industry. Nor is he intending to leave Finland.

‘I would never have guessed that I would end up in Finland, maybe in Washington, rather. However, the quality of life is good here and the saunas are the best’, Addison sums up.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institute or the United Nations University.

This article is republished with permission from Kehitys-Utveckling. Read the original article (in Finnish).

Translated from Finnish by Eeva Nyyssönen

Join the network

Join the network