Policy Brief

Growth, employment, and poverty in Latin America

Some questions have been present since the very first days of development economics but have gained increased attention in recent years: Has economic growth resulted in gains in standards of living and reductions in poverty via improved labor market conditions? How do the rate and character of economic growth, changes in the various employment and earnings indicators, and changes in poverty and inequality indicators relate to each other? Does progress take place even in circumstances of high inequality?

Some questions have been present since the very first days of development economics but have gained increased attention in recent years: Has economic growth resulted in gains in standards of living and reductions in poverty via improved labor market conditions? How do the rate and character of economic growth, changes in the various employment and earnings indicators, and changes in poverty and inequality indicators relate to each other? Does progress take place even in circumstances of high inequality?

Average growth of GDP per capita in Latin America during the 2000s was just under 3%, well above the corresponding rate in OECD countries

The rate of improvement in labor market indicators across Latin America during the 2000s was exceptional

Over the 2000s poverty and extreme poverty were reduced in fifteen of the sixteen countries studied

To answer these questions an in-depth study of the multi-pronged growth-employment-poverty nexus based on a large number of labor market indicators (twelve employment and earnings indicators and four poverty and inequality indicators) for sixteen Latin American countries (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Honduras, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, El Salvador, Uruguay, and Venezuela) was undertaken.

Remarkable progress across the region

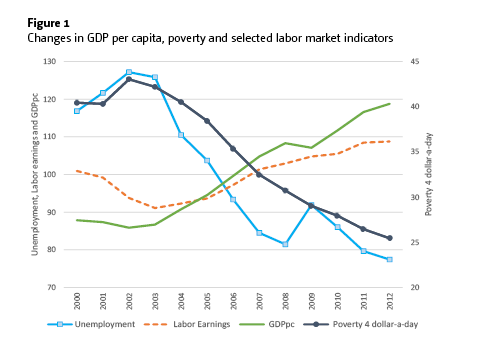

There has been remarkable progress in all three aspects of the growth-employment-poverty nexus across the Latin American region (see Figure 1):

Growth: All sixteen countries achieved positive rates of annual growth of real GDP per capita during the 2000s, ranging from 1% a year in Mexico to 5.6% a year in Panama and Peru. The regional average for the sixteen countries was just under 3%, well above the annualized rate of growth of GDP per capita in OECD countries, which was 1.0% a year.

Labor market indicators: The rate of improvement in labor market indicators was exceptional. All 16 of the labor market indicators improved in Bolivia, Brazil, and Peru, 15 of the 16 improved in Panama, and the majority of the labor market indicators improved in all of the other countries except for one.

Poverty rates: Using the 4 and 2.5 dollars-a-day poverty lines (‘poverty’ and ‘extreme poverty’), we found reduced rates of poverty and extreme poverty in fifteen of the sixteen countries. On average, extreme poverty fell 45% while poverty declined 37%. Only one Latin American country registered an increase in its rate of poverty.

In short, the 2000s were a time of strong improvement in the growth-employment-poverty nexus in the great majority of Latin American countries. The only exception to this pattern was Honduras, which was simultaneously affected by the international crisis and episodes of political instability.

In short, the 2000s were a time of strong improvement in the growth-employment-poverty nexus in the great majority of Latin American countries. The only exception to this pattern was Honduras, which was simultaneously affected by the international crisis and episodes of political instability.

Why did some countries progress more than others?

But not all improvements were equal in size or caused by the same things. To understand why some countries progressed more in certain dimensions than in others, additional analyses were performed, from which the following five lessons can be drawn.

- Growth was associated with improvements in labor market indicators, but the relationships were weak (not tightly correlated).

- Some macroeconomic factors played a key role in improving labor market conditions in some countries, although they were absent in others. The single most important factor was the commodity boom during the 2000s, which benefited most countries in South America. However, other countries like Panama and Costa Rica did not enjoy it but were equally successful in improving labor market conditions.

- Improvements in employment and earnings were clearly associated with reductions in poverty.

- When economic growth was faster, employment and earnings indicators and poverty and inequality indicators improved more rapidly. Additionally, as labor market conditions improved, poverty was reduced. However, the magnitude of these effects and the patterns over time varied substantially from country to country.

- The patterns of changes in labor market earnings were strongly progressive: In most countries the changes in labor earnings in percentage terms were larger for the poorer deciles.

Improving employment earnings should be a key goal for governments seeking reductions in poverty levels.

Policies put in place to achieve economic growth must be balanced with those that improve employment conditions and social programs.

Policy makers must now confront the challenge of achieving economic growth without the tailwind of the commodity boom that took place at the beginning of the century.

Growth without commodities

The post-2012 period seems to be marked by more heterogeneous country experiences than the 2000-2012 period analyzed in this project. Countries from South America are facing the challenge of achieving economic growth without the tailwind of the commodity boom that took place at the beginning of the century. While policies to achieve economic growth are being put into place, the channels to improve employment conditions and social programs should remain open and be enhanced: this is the most important way for economic growth to help reduce poverty, the single most important objective these countries can pursue.

Join the network

Join the network